The poet and playwright Mary Balfour was born in Derry circa 1778. She was – as her surname suggests – of Ulster Scots descent, and yet her family was not Presbyterian (like most Ulster Scots) but Anglican. Indeed, her father was a Church of Ireland minister. As an adult, she ran a school with her sisters – first in Limavady and later in Belfast. She also got caught up in the antiquarian movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: she learned Irish, deeply immersed herself in Irish folklore and history, and worked to promote the revival of Irish music.

Balfour contributed nine sets of lyrics – eight translations from old Irish-language poems and one original work – to the second (1809) edition of Edward Bunting’s General Collection of Ancient Irish Music. And her 1810 verse collection, Hope, a Poetical Essay: With Various Other Poems, features translations from Irish, as well as new poems related to Irish politics or based on Irish mythological and legendary materials. The epic poem “Kathleen O’Neil” sees Balfour re-telling the myth that a young woman called Kathleen, who was an exalted member of Ulster’s powerful O’Neil/O’Neill clan, was once abducted by the Sidhe – that is, by the supernatural “fairy folk.” Balfour adapted this same folk tale into the aptly-titled melodrama Kathleen O’Neil, which was a big hit at the Belfast Theatre in 1814. In the dramatic version of the tale, which is set in a Gaelic kingdom in Ulster in the Middle Ages, Balfour does not have Kathleen fall prey to supernatural creatures; instead, she has her abducted by McDonnel, the Scottish “Lord of the [Western] Isles”, who is aided by his Scottish henchmen and a perfidious Irish collaborator called Ferdarra.

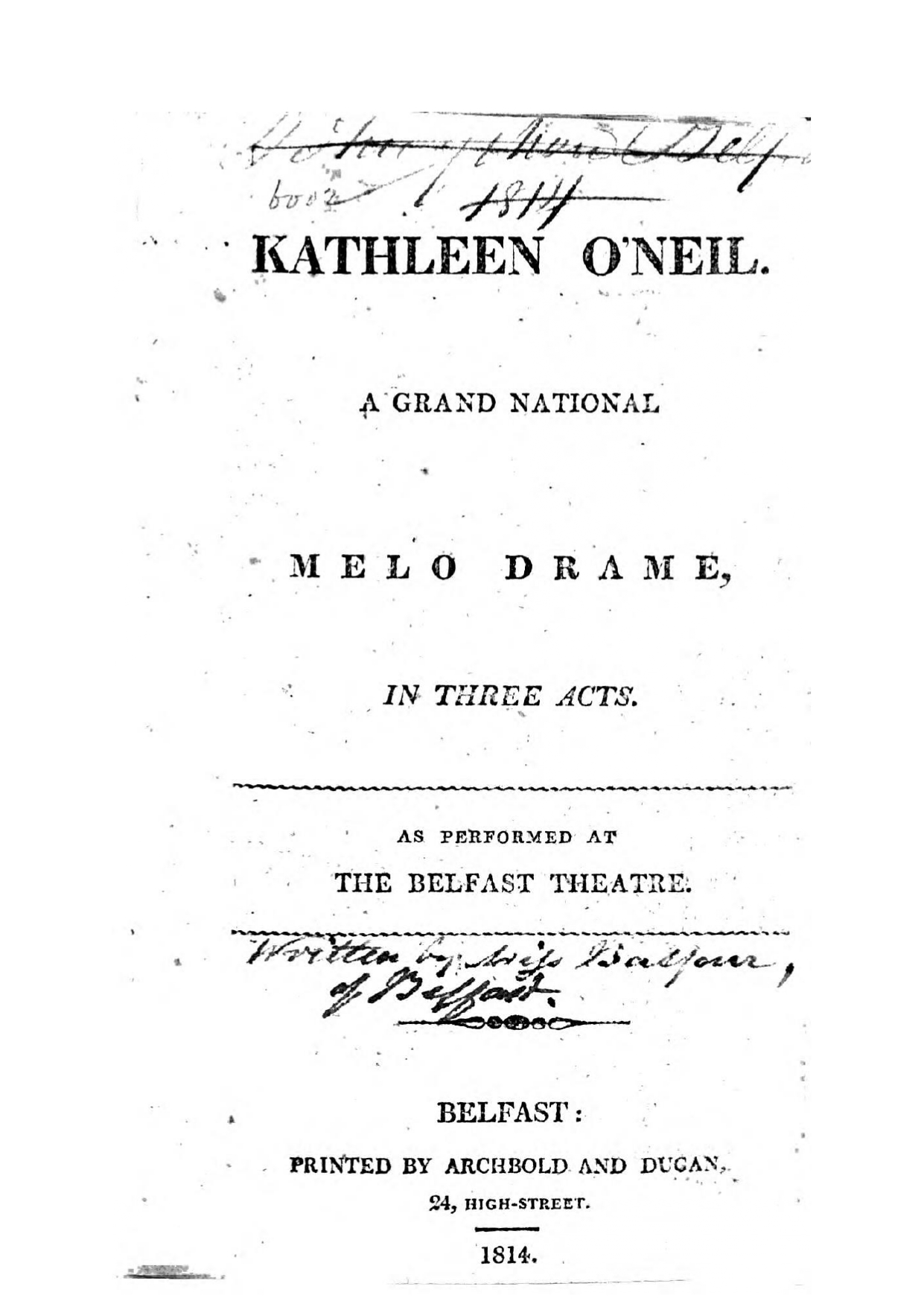

Kathleen O’Neil, which was Balfour’s only play, is significant for several reasons. First, it is an example of an Irish playwright creating a script based on Irish mythological and legendary materials long before the Revivalists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries became famous for doing so. Second, she anticipates many of the tropes associated with later Irish melodramas written by the likes of Dion Boucicault, Hubert O’Grady, J.W. Whitbread, and P.J. Bourke. These tropes include the inclusion of a centrally-featured “cheeky Irish rogue” character, strong (arguably overwhelming) patriotic sentiments, and new songs written to traditional Irish melodies. Third, the play sheds further light on the perspective of Ulster Scots – a demographic often overlooked in histories of Irish literature and drama. Finally, the play’s publication history speaks to the marginalisation of Irish women playwrights over centuries. In the wake of the play’s successful premiere run, the script was published by the Belfast firm of Archbold and Dugan. Sadly, the publishers seem to have believed that “no one would want to buy a play written by a woman”, so they provided no author’s name anywhere on or in the published text. (As can be seen in the image on this webpage, in the copy of the book in the British Library, someone has helpfully written on the title page “Written by Miss Balfour, of Belfast”.) Despite the publisher’s obscuring of Kathleen O’Neil’s authorship, the play did have an afterlife and one in which Balfour was clearly acknowledged: in 1832, the play was adapted by the Irish-American writer George Pepper, and this adaptation had significant success during its runs in Philadelphia and New York. Happily, Pepper, in the preface to his adaptation, advertises his profound debt to Balfour; he makes clear that he borrowed liberally from her play and pays handsome tribute to the “spirited poetry … and eloquent prose” created by this “gifted, patriotic … authoress”.

Plays

Find out more

For more on this playwright from an Irish Studies perspective, see my book chapter on her in the essay collection The Golden Thread: Irish Women Playwrights, 1716-2016 – Volume One (1716-1992).