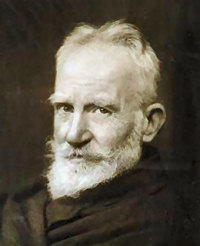

At the age of 75, Bernard Shaw told an interviewer that the happiest moment of his life was when as a child his mother informed him that his family was moving from Synge Street in the Dublin city centre to a cottage on Dalkey Hill in south County Dublin. The young Shaw was so excited, because he already knew (and treasured) the magnificent view that is available from Dalkey Hill: the Wicklow Mountains and Killiney Bay to the south, the Hill of Howth to the north, and Dalkey Island and the Irish Sea directly below. Throughout his career, Shaw always insisted that it was “the beauty of Ireland” that gave Irish people their distinctive perspective, and, in his own case, he believed that it was the beauty of this particular view that helped to shape him into the visionary iconoclast that he was.

Indeed, upon receiving the Honorary Freedom of Dublin at the age of 89, Shaw told journalist James Whelan, “I am a product of Dalkey’s outlook.” As Shaw approached the end of his life, he was eager to emphasize the importance of his Irish formative years to his work. In an article published three years later (and two years before his death), he declared, “Eternal is the fact that the human creature born in Ireland and brought up in its air is Irish … I have lived for twenty years in Ireland and for seventy-two in England; but the twenty came first, and in Britain I am still a foreigner and shall die one.”

Those who know Shaw by reputation as a writer of English society plays may be surprised to learn that he regarded himself as so thoroughly Irish, even after living in London and Hertfordshire for decades. While one might expect to see evidence of Shaw’s Irishness in his three plays set in Ireland – John Bull’s Other Island (1904), O’Flaherty, VC (1917), and Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman (1921) – his Irish perspective is also manifest in his plays set outside of his native country. As I argue in my book, Bernard Shaw’s Irish Outlook, Shaw often uses Irish and Irish Diasporic characters to express his Irish outsider perspective regarding the English and, indeed, life. And he sometimes uses what I call Surrogate Irish characters for the same purpose (these are non-Irish characters who Shaw imbues with qualities that he routinely associates with Irishness in his other plays or his journalism). Examples of such Surrogate Irish characters include the title character from Saint Joan, the long-livers from Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman, and Napoleon from The Man of Destiny; all of these characters occupy an adversarial, crypto-Irish role when confronted with the English characters (or characters of English descent) included in these works.

Between Shaw’s use of Irish, Irish Diasporic, and Surrogate Irish characters, and his frequently satirical depictions of the English (including in Pygmalion (1913), the basis for the classic musical My Fair Lady), it is clear that R.F. Dietrich was right when he recently contended that Shaw “wrote always as an Irishman.”

Plays

- Arms and the Man (1894)

- John Bull’s Other Island (1904)

- Pygmalion [1916 Edition] (1913)

- O’Flaherty, VC (1917)

- Saint Joan (1923)

- ALTERNATE VERSIONS OF THREE CLASSIC PLAYS: Man and Superman (1903) / Fanny's First Play (1911) / Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman (1921)

Find out more

For more on this playwright from an Irish Studies perspective, see my book Bernard Shaw’s Irish Outlook (2016).